In the last post, as I began to unpack monasticism and asceticism with C S Lewis’s help, I took a passage from his science fiction novel That Hideous Strength as a window into the way that war, by shaking all our self-interests and focusing us on a higher goal, can give us a new vision and focus for life. I concluded, drawing from a phrase of Lewis’ in that book: “‘The immense weight of obedience’ involved in asceticism, too, can attune us more finely to our relationships, relativize our petty anxieties and cares, and help us live our earthly, human lives with more zest and appreciation.” Now, to continue:

Why monasticism?

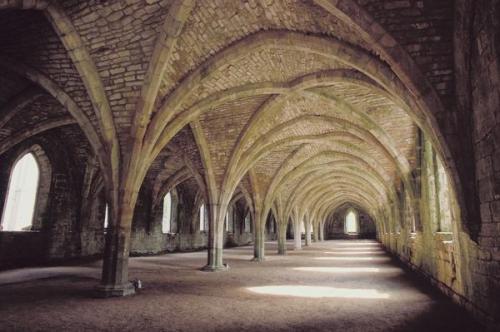

This focusing function may be a helpful general principle about asceticism. But we may fairly ask: “What makes us think the particular ascetic modes of monasticism have any answers on our modern problems? They’re so . . . medieval! Stone cloisters, hard beds, celibacy, rising at ungodly hours to chant Psalms in Latin? Really? This is the balm for our ills?”

Lewis plumbs the depths of self

Lewis, in the year leading up to his conversion, struggled mightily with his “flesh” – and even more with spiritual pride, a sin the monastic fathers unanimously agreed was among the worst, and especially tending to beset those making efforts in their lives to achieve spiritual progress.

From early on, as he struggled toward conversion, Lewis also appreciated the asceticism of the Middle Ages. Continue reading

Medieval Wisdom for Modern Christians

Medieval Wisdom for Modern Christians