Here is the third of the five potential “dyad topics” for the projected seminar on Christian humanism (again, WordPress can’t handle the auto-numbering in Word docs. Sigh) Continued from part I:

- Faith and reason

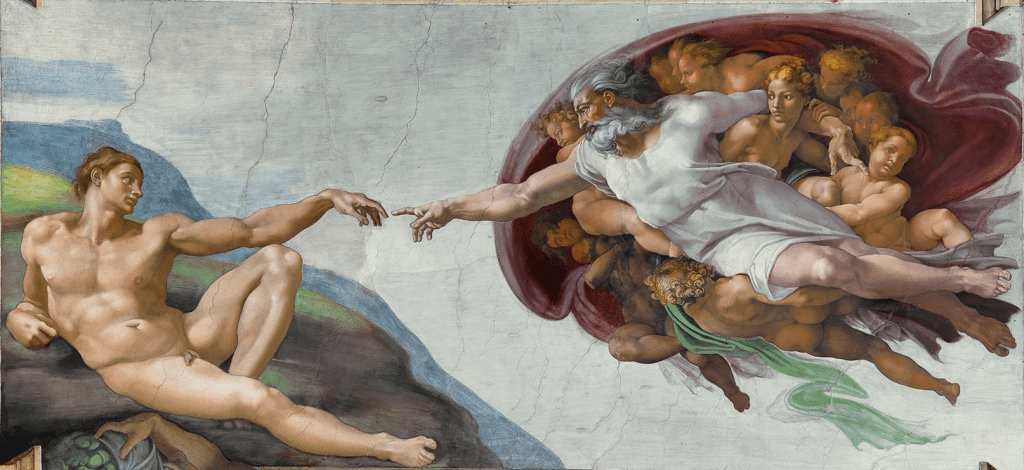

- Reason and the image of God in humanity

- The role of reason in the carrying out of the creation mandate (for human flourishing)

- Illumination and education in early Christian soteriological understanding

- The pendulum of claims for reason

- Tertullian vs. Clement on the value of philosophy

- Seminal Logos understanding

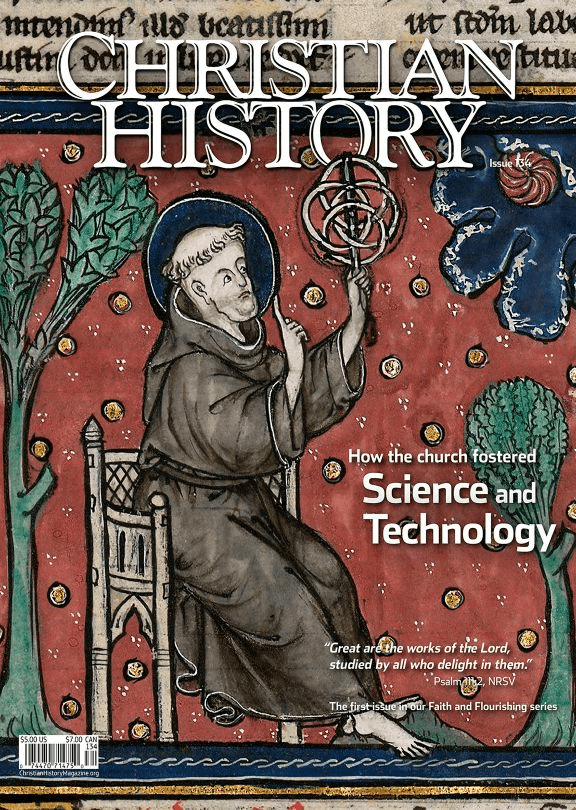

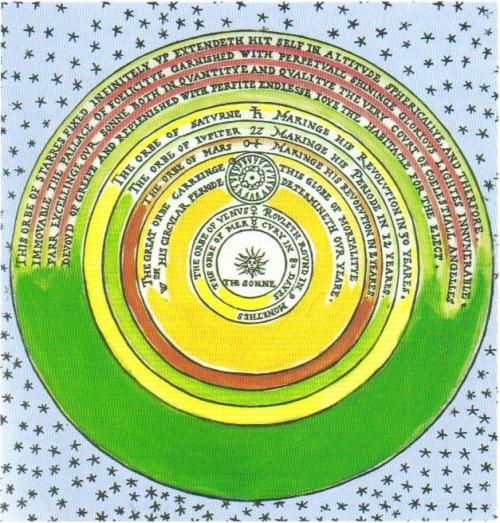

- Augustine, reason and its limitations; the autonomy of scientific knowledge and the critique of bad Christian scientific reasoning

- Anselm, “faith seeking reason” – modest claim

- Aquinas – moderate claim

- Late scholasticism – reason maximized, atrophied, and arrogant – seeking to bring all knowledge under reason’s command

- The nominalist critique

- The renaissance humanist critique

- The Lutheran critique: Luther against the philosophers

- The recovery of scholasticism under Melanchthon and the rise of Protestant scholasticism

- Positivist, naturalist anti-humanisms of wartime

To offer historical explanations for the standoff, which this paper tries to do, is not the same as explaining the individual motives of those who engage such issues today. But it is a good way to see that contemporary stances represent an amalgamation of discrete attitudes, assumptions, and convictions, and that the components of this amalgamation all have a history.

To offer historical explanations for the standoff, which this paper tries to do, is not the same as explaining the individual motives of those who engage such issues today. But it is a good way to see that contemporary stances represent an amalgamation of discrete attitudes, assumptions, and convictions, and that the components of this amalgamation all have a history. Medieval Wisdom for Modern Christians

Medieval Wisdom for Modern Christians