Here is the third of the five potential “dyad topics” for the projected seminar on Christian humanism (again, WordPress can’t handle the auto-numbering in Word docs. Sigh) Continued from part I:

- Faith and reason

- Reason and the image of God in humanity

- The role of reason in the carrying out of the creation mandate (for human flourishing)

- Illumination and education in early Christian soteriological understanding

- The pendulum of claims for reason

- Tertullian vs. Clement on the value of philosophy

- Seminal Logos understanding

- Augustine, reason and its limitations; the autonomy of scientific knowledge and the critique of bad Christian scientific reasoning

- Anselm, “faith seeking reason” – modest claim

- Aquinas – moderate claim

- Late scholasticism – reason maximized, atrophied, and arrogant – seeking to bring all knowledge under reason’s command

- The nominalist critique

- The renaissance humanist critique

- The Lutheran critique: Luther against the philosophers

- The recovery of scholasticism under Melanchthon and the rise of Protestant scholasticism

- Positivist, naturalist anti-humanisms of wartime

- Faith and reason in the history of science

- Faith supporting science

- Medieval table-setting

- The 17th– and 18th century scientific revolution

- Faith and science at odds

- Science vs. faith in the Enlightenment

- 19th-century intensifications

- The supposed warfare of science with theology (A. D. White)

- Faith and science reconciling

- Grant, Harrison, Lindberg, and other modern Christian historians and philosophers of science setting the record straight, debunking White

- Templeton Foundation – Biologos

- Science in the Church initiative

- Faith supporting science

- Modern and postmodern takes on the competence and reliability of reason vis-à-vis faith

- Postmodern critical theory, which has seen appeals to reason as cover for attempts to exert social power. All truth-claims are constructed. There is no access to a truth that corresponds absolutely to reality. Everything is a language game.

- Christian attempts to accept parts of the postmodern critique but move to a more balanced stance: critical realism, suggesting that we have access to reality to a certain extent, but that this is unavoidably colored by previous commitments – a statement as true of scientific exploration as of theological discourse: “In theology, critical realism is an epistemological position adopted by a community of scientists turned theologians.[citation needed] They are influenced by the scientist turned philosopher Michael Polanyi. Polanyi’s ideas were taken up enthusiastically by T. F. Torrance, whose work in this area has influenced many theologians calling themselves critical realists. This community includes John Polkinghorne, Ian Barbour, and Arthur Peacocke.[1]”

In the social-scientific fields, critical realism has also addressed epistemological matters related to science: “Critical realism is a philosophical approach to understanding science initially developed by Roy Bhaskar (1944–2014). It specifically opposes forms of empiricism and positivism by viewing science as concerned with identifying causal mechanisms. In the last decades of the twentieth century it also stood against various forms of postmodernism and poststructuralism by insisting on the reality of objective existence. In contrast to positivism’s methodological foundation, and poststructuralism’s epistemological foundation, critical realism insists that (social) science should be built from an explicit ontology. Critical realism is one of a range of types of philosophical realism, as well as forms of realism advocated within social science such as analytic realism[1] and subtle realism.[2][3]

- Sociology of knowledge: Postsecularism

- Habermas and postsecularism: “The term “postsecular” has been used in sociology, political theory,[1][2] religious studies, art studies,[3] literary studies,[4][5] education[6] and other fields. Jürgen Habermas is widely credited for popularizing the term,[7][8] to refer to current times in which the idea of modernity is perceived as failing and, at times, morally unsuccessful, so that, rather than a stratification or separation, a new peaceful dialogue and tolerant coexistence between the spheres of faith and reason[9] must be sought in order to learn mutually.[10] In this sense, Habermas insists that both religious people and secularist people should not exclude each other, but to learn from one another and coexist tolerantly.[11][12] Massimo Rosati says that in a post secular society, religious and secular perspectives are on even ground, meaning that the two theoretically share equal importance. Modern societies that have considered themselves fully secular until recently have to change their value systems accordingly as to properly accommodate this co-existence.”[13]

- Taylor and “postsecularism”: Charles Taylor’s A Secular Age is also frequently invoked as describing the postsecular,[14] though there is sometimes disagreement over what each author meant with the term. Particularly contested is the question of whether “postsecular” refers to a new sociological phenomenon or to a new awareness of an existing phenomenon—that is, whether society was secular and now is becoming post-secular or whether society was never and is not now becoming secular even though many people had thought it was or thought it was going to be.[15][16] Some suggest that the term is so conflicted as to be of little use.[17] Others suggest that the flexibility of the term is one of its strengths.[18]

- Faith and reason in higher education

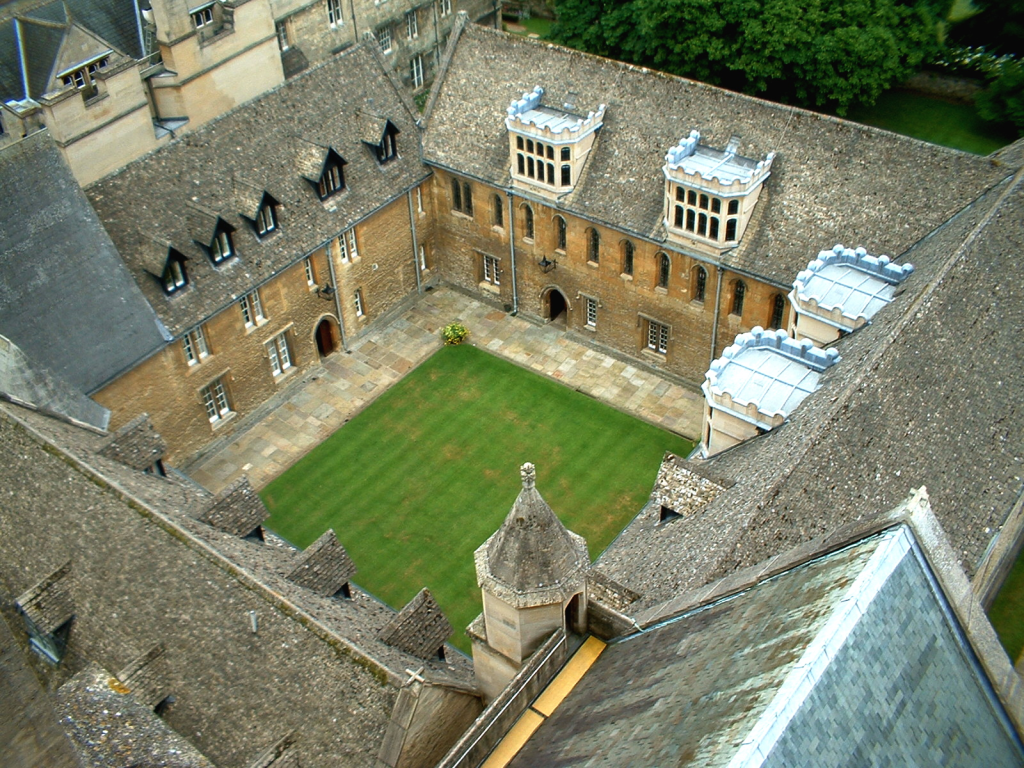

- The building of the university in the Christian West, on Christian humanist foundations (e.g. Jens Zimmermann, article in Christian History #139 [2021]: Hallowed Halls, “Restoring the divine likeness: Christian humanism and the rise of the medieval university.”Cf. Marsden’s recommendation of that article and issue in a recent Christian Scholars Review roundtable and his article on faith and reason [and fundamentalism] in the history of Wheaton College)

- The secularization of the university, in which Christian administration and faculty were complicit (e.g. Marsden, Soul of the American University; Schwehn: Exiles from Eden)

- The failure of the (rationalist, naturalist) secular university (e.g. John Sommerville, Decline of the Secular University – especially the chapter “Trouble defining the human”)

- The current supposed “postsecular moment” in the history of the university (Marsden, 2021 revised edition of Soul of the American University)

Continued in part III

Medieval Wisdom for Modern Christians

Medieval Wisdom for Modern Christians

Pingback: Five themes in Christian humanism (III) | Grateful to the dead