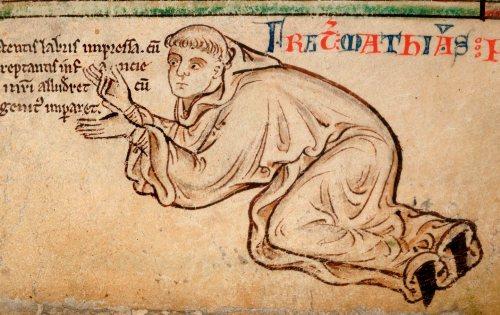

Miniature of Robin, the Miller, from folio 34v of the Ellesmere Manuscript of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales – early 1400s

Death, Desire, and the Sacramental Function of Humor in Lewis and His Medieval Sources – or, A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to Self-Denial – part III

This is the conclusion, continued from part II.

Lewis’s incarnational appreciation for the earthiness in medieval literature and drama—including the mystery plays—can be seen in an interview from months before his death. The interviewer asked Lewis about the source of the “light touch” in his writing, even when dealing with “heavy theological themes.” Lewis responded, “I was helped in achieving this attitude by my studies of the literary men of the Middle Ages [Chaucer and Dante at least, one would think], and by the writings of G. K. Chesterton[, who] was not afraid to combine serious Christian themes with buffoonery. In the same way, the miracle plays of the Middle Ages would deal with a sacred subject such as the nativity of Christ, yet would combine it with a farce.”[1]

Those who know the medieval miracle play (or “mystery play”) tradition will recognize at once how themes of desire and death get treated in this way – with the earthy, humorous touch of buffoonery and farce. As for death, I think of the crucifixion play in the York cycle. The nailers’ guild (who had the hereditary responsibility for the play) had the workmen, as they prepared the cross and pounded the nails through Christ’s hands and feet, keep up a stream of complaints at the difficulty and boredom of the work, oblivious to the divine significance of what they were doing.

In his Life of Christ, Bonaventure (1221–74) had counseled: “You must direct your attention to these scenes of the Passion, as if you were actually present at the Cross, and watch the Crucifixion of our Lord with affection, diligence, love, and perseverance.” The plays helped their audiences do this by marrying the sublime and the ridiculous, heightening the bizarre reality of a God who becomes human and dies at the hands of those he created.

One might find here the same sort of what we might call “sacramental use of humor” we find in Lewis’s treatments of Eros and death. This is a farcical way of talking about our bodily, material lives so as to both challenge our bodies’ insistent claims to ultimacy and remind us that our bodily experiences point beyond our proximate desires to the desire for heaven. “Sacramental humor” thus reinforces the truth that our God, who came to us bodily in the Incarnation, still meets us in our bodies.

I would argue that this is in fact one of the most central insights of medieval faith, fixated as it was on the Incarnation. Continue reading

Many thanks to Scot McKnight for hosting Dave Moore’s interview with me on my new book, posted here today: at

Many thanks to Scot McKnight for hosting Dave Moore’s interview with me on my new book, posted here today: at

Medieval Wisdom for Modern Christians

Medieval Wisdom for Modern Christians