For those who enjoyed my faith & science history series over the past couple of weeks, there’s a treasure trove awaiting: The recent Christian History issue(s) on the same topic. You can browse the issue in full color and download pdfs of individual articles here.

Which reminds me to say . . .

. . . if I had a nickel for every time someone has said they didn’t know that Christian History had re-started after its then 26-year run ended in the fateful year 2008 . . . well, I’d be able to buy a fancy coffee or two. And little did anyone know – leastwise the magazine’s editors and parent (non-profit) organization – that in 2022 we’d be cruising into CH’s 40th anniversary year (special anniversary issue coming – keep an eye out at this link!).

But since 2011, the magazine has indeed lived again – and what a run it’s been, under the indefatigable editorial leadership of scholar/editor/writer/priest extraordinaire Jennifer Woodruff Tait. Among the topics we’ve covered just in the past few years: America’s love affair with the Bible; CS Lewis’s friends & family and their influence on him; Christian support for the common good in science, healthcare, higher education, the public square, and the marketplace; Christianity and Judaism; plagues and epidemics; Latin American Christianity; the women of the Reformation; the Quakers . . .

And for those interested in topics churchly/scientific, check out the following issues:

- The Wonder of Creation

- Debating Darwin

- Healthcare and Hospitals in the Mission of the Church

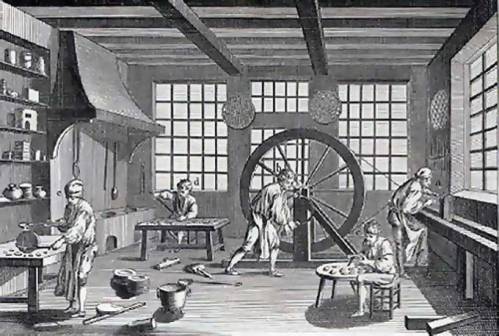

- The Christian Face of the Scientific Revolution

Hard to believe that last one, my very first issue as (short-lived) managing editor, came out a full 20 years ago! And I’m still proud of it . . .

Thanks y’all for reading my blog. I hope you enjoy these resources!

Medieval Wisdom for Modern Christians

Medieval Wisdom for Modern Christians