*AS OF 6:15 CST TODAY (DEC 5), THE INTERNET MONK SITE, WHICH WAS DOWN FOR THE AFTERNOON, IS UP AGAIN. CHECK IT OUT: THE LINK BELOW IS WELL WORTH ACCESSING.

Friend John Armstrong posted an interesting discussion I’d like to pass on to readers:

*AS OF 6:15 CST TODAY (DEC 5), THE INTERNET MONK SITE, WHICH WAS DOWN FOR THE AFTERNOON, IS UP AGAIN. CHECK IT OUT: THE LINK BELOW IS WELL WORTH ACCESSING.

Friend John Armstrong posted an interesting discussion I’d like to pass on to readers:

Posted in Resources for Radical Living

Tagged chaplaincy, death, ecclesiology, John H. Armstrong, Mark Galli, missional, pastoral care, pastors

Mark Galli, I love you as a brother in Christ. As managing editor in the flagship evangelical Protestant publication, Christianity Today, you have presented an impassioned and powerful case for why evangelical Protestants tempted to cross the Tiber and join with the Roman Catholic Church should think twice . . . and then remain in the evangelical fold. While I balk at some of your historical characterizations, I affirm your central point.

A word on those historical characterizations. Mark assert confidently: “Huge segments of the church were bound to the chains of works righteousness before the Holy Spirit ignited the Reformation.”

Really? “Huge segments”? While at Duke University (fountain of all wisdom, funded by tobacco money . . . and surprisingly loyal, in at least many parts of the Divinity School, to the Great Tradition), I learned different from David Steinmetz, the (Protestant) historian of the Reformation at Duke . . . unless, David, I interpreted your lectures wrongly:

Friends, I’m not sure what to make of D. A. Carson‘s recent piece on spiritual disciplines in the pages of Themelios. Let’s say I’m processing. I see in his reflections both unfortunate Protestant bias (I think he misses entirely the intense Christocentrism of medieval mystics such as Julian of Norwich, which his colleague Carl Trueman in an earlier piece in the same organ did NOT miss), and acute gospel wisdom (“disciplines” must not mean gritting our teeth and doing things under our own steam–a point he makes later in the piece). I’d be interested in comments from y’all. Below is a sample. The whole article may be found here.

How shall we evaluate this popular approach to the spiritual disciplines? How should we think of spiritual disciplines and their connection with spirituality as defined by Scripture? Some introductory reflections:

(1) The pursuit of unmediated, mystical knowledge of God is unsanctioned by Scripture, and is dangerous in more than one way. It does not matter whether this pursuit is undertaken within the confines of, say, Buddhism (though informed Buddhists are unlikely to speak of “unmediated mystical knowledge of God“—the last two words are likely to be dropped) or, in the Catholic tradition, by Julian of Norwich. Neither instance recognizes that our access to the knowledge of the living God is mediated exclusively through Christ, whose death and resurrection reconcile us to the living God. To pursue unmediated, mystical knowledge of God is to announce that the person of Christ and his sacrificial work on our behalf are not necessary for the knowledge of God. Sadly, it is easy to delight in mystical experiences, enjoyable and challenging in themselves, without knowing anything of the regenerating power of God, grounded in Christ’s cross work.

(2) We ought to ask what warrants including any particular item on a list of spiritual disciplines. For Christians with any sense of the regulative function of Scripture, nothing, surely, can be deemed a spiritual discipline if it is not so much as mentioned in the NT. That rather eliminates not only self-flagellation but creation care. Doubtless the latter, at least, is a good thing to do: it is part of our responsibility as stewards of God’s creation. But it is difficult to think of scriptural warrant to view such activity as a spiritual discipline—that is, as a discipline that increases our spirituality. The Bible says quite a lot about prayer and hiding God’s Word in our hearts, but precious little about creation care and chanting mantras.

Please pray for someone who has been, over the past two decades, one of the most important voices in Christian reflection on culture: Ken Myers of the Mars Hill Audio Journal. He has recently suffered a massive, life-threatening heart attack, followed by a miraculous recovery. The facts of the heart attack are laid out here and updates on Ken’s recovery are being posted here.

Please pray for someone who has been, over the past two decades, one of the most important voices in Christian reflection on culture: Ken Myers of the Mars Hill Audio Journal. He has recently suffered a massive, life-threatening heart attack, followed by a miraculous recovery. The facts of the heart attack are laid out here and updates on Ken’s recovery are being posted here.

I do not know Ken personally, but I have benefited immensely from his work at Mars Hill Audio Journal over the years. If you don’t know of this valuable resource, subscribe now! Or at least find out whether your local/college/seminary library carries the wonderful interviews this former NPR reporter has conducted over the years and produced in this journal.

Ken, my prayers and thanksgiving for you are going up to God right now. May you enjoy many more happy and productive years.

Posted in Resources for Radical Living

Tagged Christ and culture, Heart Attack, Ken Myers, Mars Hill Audio, media, NPR

Here is the finished, significantly revised and polished form of the Leadership Journal article I wrote this summer on “dark nights of the soul” in the lives and thought of C S Lewis, Mother Teresa of Calcutta, and Martin Luther (the longer forms of each person’s story are linked at the end of this post):

Here is the finished, significantly revised and polished form of the Leadership Journal article I wrote this summer on “dark nights of the soul” in the lives and thought of C S Lewis, Mother Teresa of Calcutta, and Martin Luther (the longer forms of each person’s story are linked at the end of this post):

| The following article is located at: http://www.christianitytoday.com/le/2011/fall/historydarkness.html |

A History of Darkness

The struggles of these spiritual giants yielded unexpected blessings.

Chris R. Armstrong

Monday, November 7, 2011

Christian faith is built on presence. Whether in the pillar of fire, the still small voice, or the incarnate Son, God has been Emmanuel, “with us.” He has promised never to leave or forsake us. In thousands of hymns, we have sung of an experienced intimacy with God in Christ. We have prayed, wept, and rested in his presence.

For a committed Christian, then, nothing is more devastating than divine absence, spiritual loneliness, the experience of our prayers hitting a ceiling of brass. Continue reading

Speaking of Dorothy Sayers, thanks to friend Marc Cortez over at Scientia et Sapientia for this reminder of a piece of Sayers’s writing that has become more read in recent years than perhaps anything else she wrote besides her Lord Peter Wimsey mystery stories:

Today marks Dorothy Sayers‘ 118th birthday (June 13, 1893). Writer, theologian, poet, essayist, and playwright, Sayers did it all. And, she did it amazingly well.

To commemorate her birthday, here are some excerpts from her essay on The Lost Tools of Learning. Regardless of whether you agree with her argument that we need to return to medieval models of education (and the way this argument has been used by the classical and home schooling movements), her comments on the importance of learning to think are outstanding:

“Have you ever, in listening to a debate among adult and presumably responsible people, been fretted by the extraordinary inability of the average debater to speak to the question, or to meet and refute the arguments of speakers on the other side? Or have you ever pondered upon the extremely high incidence of irrelevant matter which crops up at committee meetings, and upon the very great rarity of persons capable of acting as chairmen of committees? And when you think of this, and think that most of our public affairs are settled by debates and committees, have you ever felt a certain sinking of the heart?”

For the rest of the quotations, see here.

Following up on a previous post, this is something I cooked up while working as a “preceptor” at Duke–that is, leading seminars for students taking a course (in this case Dr. David Steinmetz’s CH13: Church History to the Reformation), in which we interacted in more depth with the primary documents.

This one’s on that Great Brain of the early church, Augustine of Hippo. It includes a few “notes to myself” about how to lead such a seminar, since as a doctoral student I was still wet behind the ears on this important matter of pedagogy. I wish I could remember which sourcebook we were using for the Augustine quotations. I could go try to figure it out from old syllabi, if anyone’s interested:

One of the first and most basic problems we have to deal with when we talk about this great North African theologian is this: [write on board] Is it AUG-us-teen or au-GUS-tin? It makes no difference to me which we say, but somewhere along the way, I was told that if you want to make it at a party with a bunch of church historians, you need to use au-GUS-tin for this man from Hippo, and reserve AUG-us-teen for the archbishop installed in England by the Pope around the year 600, who tried to bring the Celtic [or is that SSSeltic?] church into line.

In any case, it doesn’t matter to me how we pronounce it today. Saying AUG-us-teen won’t lower your grade…much.

1. Write on the board: “posse non peccare,” “non posse non peccare,” “non posse peccare.”

2. Start with the background from Latourette, to put Augustine in context with (1) the E/W distinctions S. has made, (2) some other “fathers,” (3) Augustine’s own personal history.

3. Deal with quoted sections from Augustine, below, one by one, allowing conversation to develop as it will. If this serves to jumpstart the process of “dealing with Augustine on freedom,” well and good. I needn’t return to the quotations. If things slow down, however, I can reopen with, “what about this statement: [quotation]. What is Augustine saying here and what do we think about it?”

4. Throughout the process, resist going too far off into either what we think about Augustine (though that’s inevitable) or, especially, whether Wesley (Calvin, Luther, Joe Blow) would have agreed with Augustine. It is OK to do this now and again, but as in a Bible study, let’s return to the text. We need to discipline ourselves to do that because it is often so much easier to talk about our own opinions or those of our church traditions, than to confront and work through the thought of the person we are studying.

5. For the second half (or third, or quarter, or last five minutes) of the class, survey Augustine’s thought on (1) the status, (2) person, (3) and work of Christ, as well as (4) the Holy Spirit, (5) the Trinity, (6) the Church, (7) the Sacraments, and (8) the Last Things. Continue reading

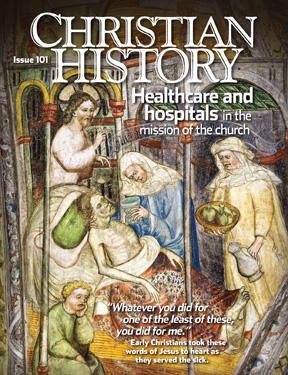

Yep. The Christian History editorial team is celebrating the printing of Issue #101: Healthcare and Hospitals in the Mission of the Church. For full access to this full-color issue (including a magnified view for us old people–just click on the magazine to enlarge), see here.

Yep. The Christian History editorial team is celebrating the printing of Issue #101: Healthcare and Hospitals in the Mission of the Church. For full access to this full-color issue (including a magnified view for us old people–just click on the magazine to enlarge), see here.

The issue tells the fascinating story of how early and medieval Christians pioneered the healthcare institutions on which we now rely, including the modern hospital.

Christian History itself is moving forward in full and glorious health. Projects in the pipeline for 2011-12 include the following:

–a guided tour of 1,000 years of worship from Constantine to Luther,

–a larger issue or even book on the history of Christianity in America,

–an issue showing how influential early African Christianity (especially North African) was in the development of the faith,

–an issue exploring the ways the church responded to the travails and malaises of industrial society from the early 1800s through the beginning World War II, and

–a special keepsake issue on the history of Christmas.

If you haven’t signed up for the magazine yet at http://www.christianhistorymagazine.org, now is the time! Tell your friends!

As Scot McKnight says over at his Jesus Creed blog, this is an article in the Associated

Baptist Press that ought to get some discussion:

WACO, Texas (ABP) — A rising generation of Christians intent on working for social justice must not confuse that effort with “kingdom work,” award-winning Christian author Scot McKnight said during the Parchman Endowed Lecturesseries at Baylor University’s Truett Theological Seminary.

“In our country, the younger generation is becoming obsessed with social justice,” including through government opportunities, politics and voting, said McKnight, author of The Jesus Creed: Loving God, Loving Others. “What it’s doing is leading young Christians out of the church and into the public sector to do what they call ‘kingdom work.’

“I want to raise a red flag here: There is no such thing as kingdom work outside the church — and I don’t mean the building. The kingdom is about King Jesus and King Jesus’ people and King Jesus’ ethics for King Jesus’ people. Continue reading

Posted in Resources for Radical Living

Tagged Scot McKnight, social gospel, social justice, Social work, the kingdom of God

Want to know more about Pietism's "religion of the heart"? Check out this book by some friends of mine

This is the final part of a 4-part post:

Now at last we come to Pietism itself. There are all sorts of interpretations of where Pietism came from, when it emerged in the 1600s. Some Lutherans at the time felt it was a kind of crypto-Calvinism. Others felt it had on it the taint of Anabaptism. And so forth. But this much is clear: it was a natural development out of the thought and piety of Martin Luther. And so if we want to talk about how Pietism re-introduced the historical Christian “religion of the heart,” we need to remember that as it did so, it drew on this mystical side of Luther. In fact, Philip Spener, the man usually identified as the “father of Pietism,” was, according to Karl Barth, the greatest Luther scholar since Luther. He wasn’t making things up as he went along, creating some brand new form of Christianity. He was a deeply pious Lutheran, who counseled state-church Lutherans to stay in their churches.

Of course, he didn’t want them to just stay in their churches. For many of their churches were, just like their seminaries, “dead.” That is, they were more interested in orthodoxy than in conversion of life. Spener wanted the Lutherans of his day to read their Bibles at home, to get together in small groups, to get out and live Christianly in the marketplace and the town square—to let their love relationships with God make a difference in their lives. Spener’s protégée, August Hermann Francke, took this principle and turned it into a full-blown institution, founding and running a complex in the city of Halle that included a large orphanage, a school, a printing house, job training facilities, and much more. This was a faith not only with a heart, but with hands and feet. Continue reading