Continued from part I

Opening historical salvo

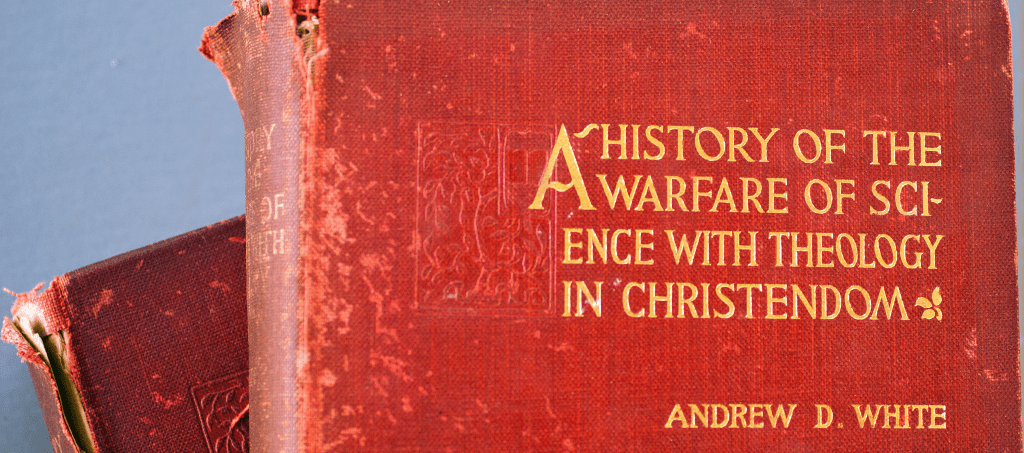

A reasonable place to start this “story in ten facts” might be with the scientific revolution—traditionally dated from the 1543 publication of Copernicus’s On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres to the 1687 publication of Isaac Newton’s Principia. As soon as we look at this revolution – the seedbed of all modern scientific disciplines—we see some potential problems with the warfare thesis.

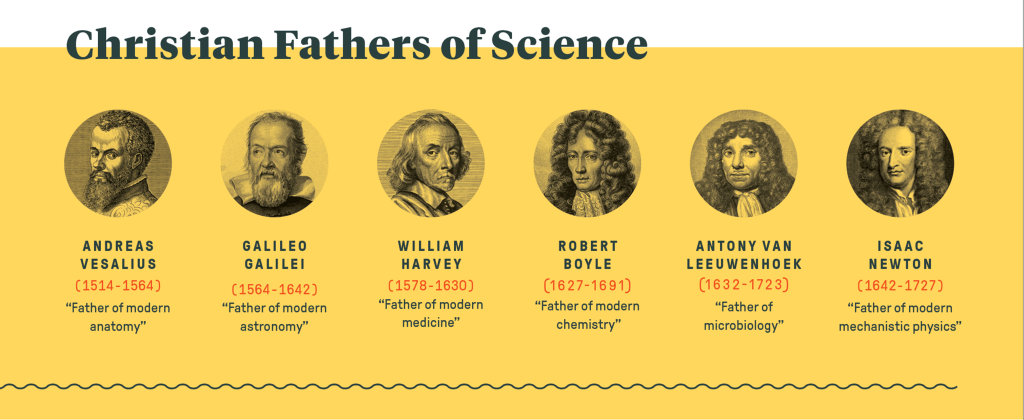

First, we notice that the scientific revolution happened before the secularizing Enlightenment—traditionally dated from the death of the French king Louis XIV in 1715 to the outbreak of the French Revolution in 1789. In other words, modern science was born in a Europe still thoroughly Christian in its thinking and institutions. That being true, it’s not surprising that almost all of the scientists who founded modern scientific disciplines during that period were themselves Christians [see illustration at the top of part I]. You’ll see a few named here – and we could include so many others, from Nicolaus Copernicus to Johannes Kepler to Blaise Pascal. Every one of these innovators was a person of faith who pursued scientific and technological innovation out of Christian motives and understandings.

I know what you’re thinking. “Ah, but what about Galileo? Wasn’t his work on the solar system suppressed by the church? Didn’t he become a prisoner to religious bigotry?” Well, no. It turns out Galileo ended up on trial before the Inquisition more because of his political naivete and lack of tact than anything else, and that the trial was more a legal dispute than a clash of beliefs. Says historian Thomas Mayer, “The notion that Galileo’s trial was a conflict between science and religion should be dead. Anyone who works seriously on Galileo doesn’t accept that interpretation any more.”

Continue reading

Medieval Wisdom for Modern Christians

Medieval Wisdom for Modern Christians