Fitting right into the modern Monty Python stereotype of medieval people as backward, ignorant, and superstitious is the assumption that especially the monks of the Middle Ages sought only supernatural explanations for things. Understanding that up to the 12th century, healthcare took place almost exclusively in the monasteries, we jump to the logical conclusion: such care couldn’t possibly have attended to the physical causes of illness. Didn’t those monks just believe that illness was caused either by demons or by the sins of the sick person? There’s a germ of truth here (pun intended), but the reality was quite different. That’s the subject of the next section of the hospitals chapter in my Getting Medieval with C S Lewis.

Fitting right into the modern Monty Python stereotype of medieval people as backward, ignorant, and superstitious is the assumption that especially the monks of the Middle Ages sought only supernatural explanations for things. Understanding that up to the 12th century, healthcare took place almost exclusively in the monasteries, we jump to the logical conclusion: such care couldn’t possibly have attended to the physical causes of illness. Didn’t those monks just believe that illness was caused either by demons or by the sins of the sick person? There’s a germ of truth here (pun intended), but the reality was quite different. That’s the subject of the next section of the hospitals chapter in my Getting Medieval with C S Lewis.

Monastic phase

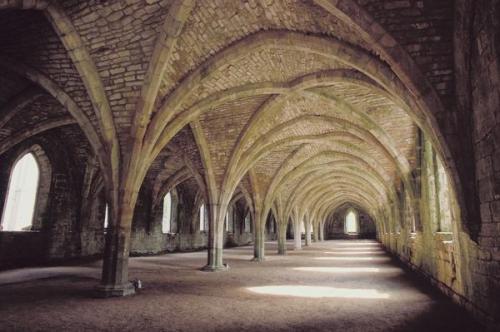

The distinctly monastic flavor of healthcare during the Middle Ages – even when it was provided by lay orders like the Hospitallers – deserves a bit more probing. From the beginning, monasteries in the West took Benedict’s cue and made caring not only for ill monks but also for needy travelers one of their primary tasks. The “stranger” was always an object of monastic charity. This “rather broad category,” says medical historian Gunter Risse, included “jobless wanderers or drifters as well as errant knights, devout pilgrims, traveling scholars, and merchants. . . .”[1] Monastic care for the stranger and the ill was formalized in the 800s during Charlemagne’s reforms, as assemblies of abbots (leaders of monasteries) gathered to reform and standardize that aspect of monastic life. At that time many of the scattered church-sponsored hostels (xenodocheia) across the Holy Roman Empire were given “regula”—quasi-monastic rules, and “monasteries . . . assumed the greater role in dispensing welfare.”

Organized, ubiquitous, stable, pious: the monasteries of the West became sites of care and of medical learning. “Benedict’s original rule ordered that ‘for these sick brethren let there be assigned a special room and an attendant who is God-fearing, diligent, and solicitous.’ This monk or nun attending the sick—the infirmarius was usually selected because of personality and practical healing skills. The latter were acquired informally through experience, as well as through consultation of texts, medical manuscripts, and herbals available in the monastery’s library or elsewhere. . . . The infirmarius usually talked with patients and asked questions, checked on the food, compounded medicinal herbs, and comforted those in need. . . .”[2]

“A rudimentary practice of surgery (‘touching and cutting’) at the monastic infirmary was usually linked to the management of trauma, including lacerations, dislocations, and fractures. Although these were daily occurrences, the infirmarius may not have always been comfortable practicing surgery on his brothers, for it was always a source of considerable pain, bleeding, and infection. Complicated wounds or injuries may have forced some monks to request the services of more experienced local bonesetters or even barber surgeons. . . .”[3] Risse notes other popular healing practices of the Middle Ages that were integrated into the monastic medical routine, including herbology, bathing (not otherwise common!), preventive bloodletting, and diagnostic examination of pulse, urine, stool, and blood.

The mention of some of these “backward” medieval medical practices may raise another stereotype many have in their heads about the Middle Ages. Just as some still believe the fabrication that medieval people believed in a flat earth, some assume that medievals did not know, and were not interested in, the physical causes of illness. Instead, the story goes, they assumed all illness came from devilish or demonic sources, or, a variant, from some hidden sin in the sick person. Continue reading →

Medieval Wisdom for Modern Christians

Medieval Wisdom for Modern Christians