Continued from part II

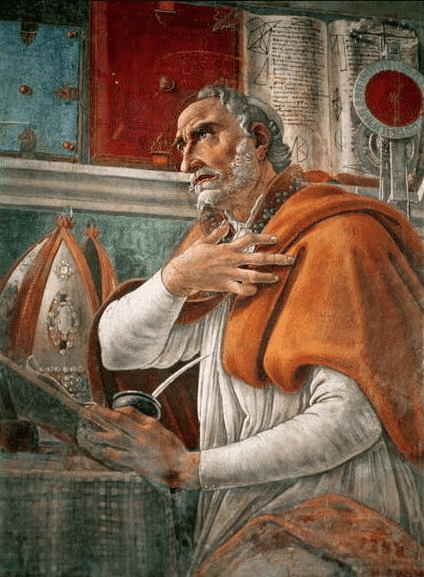

First, then, the “busyness thesis,” as read by such thinkers as Augustine of Hippo and Gregory the Great.

Augustine of Hippo described two kinds of life: the active life and the contemplative life. His reflections on the relationship between these set the theological tone for the entire era of the Middle Ages on this aspect of the relationship between spiritual and economic work—though as we’ll see later, we already find some monastic pioneers a generation or two before Augustine who were concerned with the potential for a busy life with lots of human responsibilities to crowd out the quest for personal holiness.

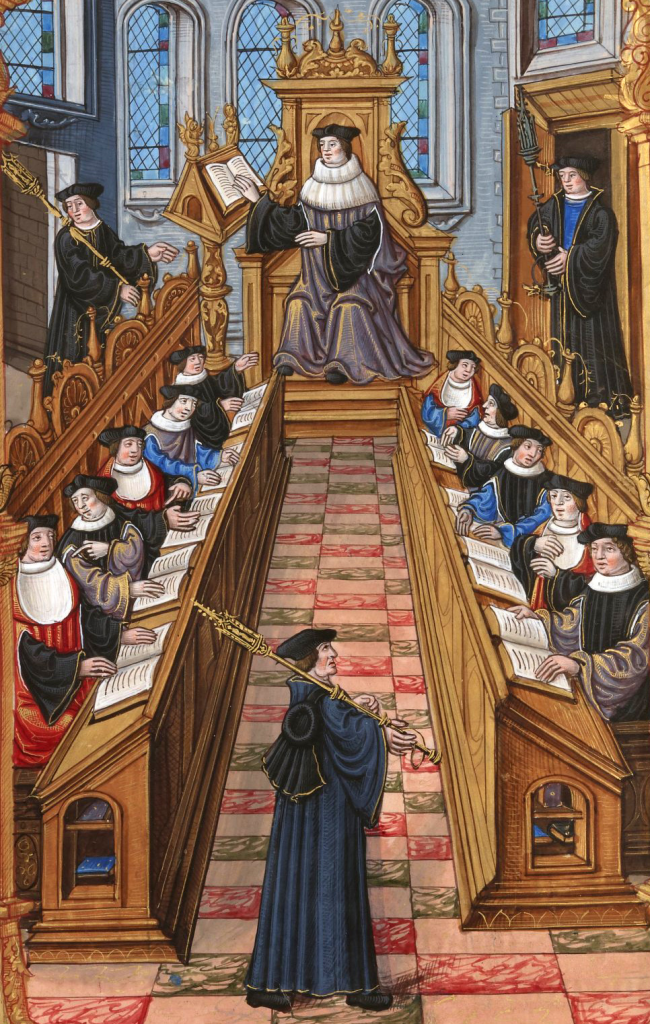

From his writings on this matter, it is clear that he sees both kinds of life as necessary and that the active life comprises most of our experience here on earth. Second, it is also clear that the contemplative life is above all desirable, unites us to our true God, and comprises tastes of heaven for us – thus the descriptions of the contemplative life in the long list of dyads in his most famous passage on the subject, below, is a kind of travel brochure or gift catalogue for the contemplative life, designed to stir up our desire for it. One may see such language as a clue to why so many entered an ascetic, and so many more a fully cloistered monastic, life in the time between Augustine and Luther: only strong desire could so move them:

Continue reading

Medieval Wisdom for Modern Christians

Medieval Wisdom for Modern Christians